Kurt Vonnegut’s rule #3 for writing short stories applies even more to film:

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

What characters want can be very simple, but they have to want something, have some kind of goal – Vonnegut’s glass of water, the mouse getting the cracker over the ledge, Nathaniel’s glass of milk, Torri’s jumping into a quarry, Wink getting to a bus, or Hushpuppy’s getting him a bite of fried gator tail. Characters can want multiple things as they go along, but when they don’t have an overall goal the audience is denied the pleasure of expectations – thwarted, mysterious, or fulfilled.

Assignment: Make a 2+ minute action sequence following a character as they move from one place to another and at the end do something, maybe with their hands. The action is linear and purposeful – it is not a montage.

Due: December 11/12

Required:

- a useful and varied mix of shots – establishing, medium, close-up; static, moving; low angle, high angle; rack focus (FiLMiC Pro) – think of all the things we looked at in Lola (who’s got a crane? selfie stick!)

- framing/edits that follow the 180° rule and are aware of consistent lateral direction

- at least one “cut on motion,” maybe one of which is “walking (moving) through the camera”

- mechanically smooth tracking shots (e.g., slider / dolly / skateboard / car / bike / shopping cart / rolling-truck-with-no-driver-and-camera-duct-taped-to-window )

- handheld-seeming shots

- jump cuts

- rule of thirds

- keep the camera moving

- cuts to POV shots, where it’s clear we’re seeing what the character is looking at as they move along

- at least one shot you’re technically proud of

- give it some air – starts black with faded-in sound, ends black

- no need for title or credits unless they add to what you’re doing

You can crosscut a couple times to the goal if that’s fun/effective, and crosscut more if it’s a chase scene, but not so much that you avoid the problem of how to vary the mix of shots and tell the story linearly.

No diegetic sound – just slam in a music soundtrack. Advanced students can tweak this requirement if they know what they’re doing.

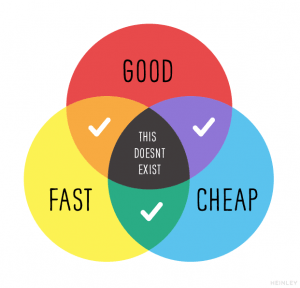

For some people this is an exercise, learning to think about how to shoot a sequence. For others this can turn into something aesthetically complete, interesting, and satisfying. Either is fine – no need to shoulder the burden of art unless you want to.

You can create film crews for shooting and then share the resulting footage. Everybody, however, edits their own final cut. Most people in the past have just done the assignment on their own, with one cameraperson and one actor, and it works just fine.

When transferring your clips to iMovie, iMovie itself is pretty good at seeing into your phone or camera (using USB – see iMovie Essential Training, Chapter 1). Image Capture gives you more control, though.